Kawkab Hefni Nassif

Surgeon

Dr. Kawkab Hefni Nassif is a 20th-century woman pioneer of the medical profession in Egypt, and the younger sister of Malak Hefni Nassif, one of the pioneers of the feminist movement in Egypt. Kawkab traveled on a study mission to England in the 1920s, during which she earned a degree in medicine, then returned to work as a medical doctor at Kitchener Hospital, to become one of the first Egyptian women to practice medicine, and one of the first women in Egypt to obtain the membership of the Egyptian Medical Syndicate. Earlier in her life, Kawkab joined the protests of the 1919 Revolution, which led to her being expelled from school. In the interview, Kawkab shared her academic and career journey.

Kawkab spoke about the impact of her elder sister, Malak Hefni Nassif, on her character, and the important role Malak played in her upbringing. Due to their mother’s illness, Malak took over the responsibility of caring for Kawkab, who in turn learned a lot from Malak, especially about Arabic poetry. Malak used poetry to help Kawkab overcome the bullying she was subjected to because of her darker skin color. Kawkab also spoke about her immense grief for losing Malak, who died at a young age, when Kawkab was only 18. Recalling the day Malak died, Kawkab recounted, “I was at the boarding school the night she died, and I started crying for no reason. When the supervisor asked me what was wrong, I told her my tooth hurt. I had to say that because I did not know why I was crying. There was no reason for me to cry. The supervisor gave me some medicine, then two hours later, woke me up, and told me that the school called my family, and my brother was coming to take me to the doctor. I got dressed and went down. It was late at night. My brother Essam, who was 17 at the time, was crying. I kept telling him that I was not that sick. He said that dad hit him because he got kicked out of school, and dad never hit anyone. It was a horrible day. We took a carriage home. There were no cars or taxis then. I entered the house, and found my sister Hanifa lying on the bed crying, so I looked at my mother. It was then when she told me that my sister Malak died. I was stunned. They began the traditional funerary rituals, and turned the carpets upside down, and things like that. All the schools were closed, and everybody walked at the funeral procession. More than 20,000 people walked from Shubra to al-Imam al-Shafie. I could not believe that she was dead, and until this moment, I still cannot believe it.”

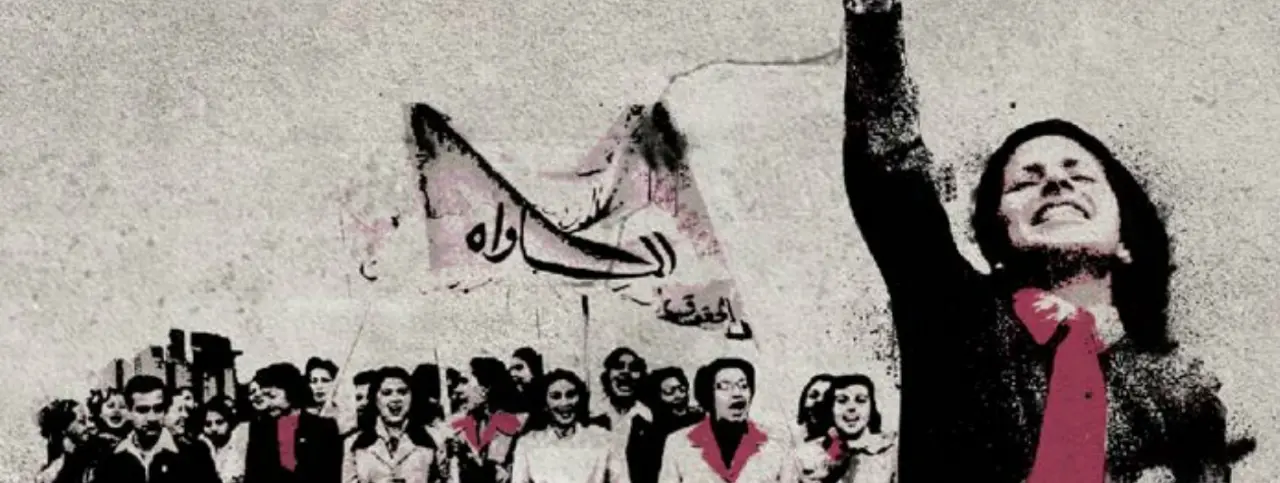

As for her education, Kawkab attended a boarding primary school until she was 13 years old because her father was working in Tanta at the time. Despite her young age, she was enrolled into al-Saniya School soon after completing her primary education. As soon as the 1919 Revolution erupted, Kawkab joined the protests. She mobilized for the demonstrations, and marched outside the school with Mounira Rafael, among others of her schoolmates. The girls were then joined by students from the nearby schools. Kawkab recalled her deep passion for the 1919 Revolution, and added that she felt furious at the presence of the English soldiers, saying, “I was young I know, but I used to boil with anger at the sight of those trucks carrying the English brigade soldiers. I used to wonder, in secret of course, when I would see Egyptian soldiers instead.”

The School Principal, Ms. Harding, expelled Kawkab and Mounira Rafael as a result of their participation in the Revolution. Kawkab stayed at home for a year, until the New Helmeya Public School was established. She recalled, “this was also a governmental school, so I could not get in, because whoever got expelled from one governmental school was not allowed to enroll in another governmental school. I submitted a request, which was endorsed by everyone at the Ministry of Education. They all nominated me to enroll. But the Principal, who was transferred from al-Saniya School to al-Helmeya School, denied my request. She insisted that the law was clear, and that since I was expelled, I should not be allowed to attend this school under any circumstances. She also kept saying that I hated the English, but people told her not to worry about the English government. I was not even 14 years old at the time. I would not topple the English government at such a young age.” Kawkab managed to enroll into al-Helmeya school, where she studied alongside Karima al-Saeed, Aziza al-Saeed, Wagiba al-Sadiq, Souad Reda, Souad al-Muweilhi, Nabila Youssef, and Isabel Hanna.

In 1919, and almost forty days after the king’s death, Kawkab’s father died. Recalling her mother’s strength and courage in the face of this adversity, Kawkab said, “my mother was brave and strong. When she told me that my father died, I fell to the ground. I felt as if the entire world was about to die. She poured a cup of cold water on my head, and kept saying ‘you will live, you will grow up, you will learn, and you will become a human being.’ My dad did not get to see his father. His father died before he was born, when his mother was still a newlywed. My grandfather was a scholar at al-Azhar.”

Later, Kawkab was nominated to travel on a four-year scholarship to England to complete her secondary education, and earn her English diploma, as part of the Kitchener mission. Two students were nominated from each of al-Saniya and al-Helmeya schools, and two others from the foreign schools, such as the Sacré Coeur French School, and the American College. The Ministry of Education nominated Kawkab, but the Principal Ms. Harding objected again, on the basis of Kawkab’s hatred of the English. Kawkab recalled that it was Sir Saad Barada who promised her that she would travel, nonetheless. In 1922, Kawkab was on the ship leaving for England with some of her classmates, among whom was Anisa Nagi from al-Helmeya School, Tawhida Abd al-Rahman from al-Saniya School, Habiba Owais from the Sacré Coeur, and Fathia Hamed from the Girls’ College.

After four years, Kawkab completed her school education, and attended the Faculty of Medicine. During that time, Dr. Helena Sidaros was already in England studying on an earlier mission. She requested from the Ministry of Education to be transferred to the Kitchener mission to join Kawkab and her group, and graduated one year before them. Upon her graduation, Kawkab worked at a Christian hospital. Her desire was to specialize in obstetrics and gynecology, and so she requested to be transferred to Dublin, Ireland, where there was a specialized school. She stayed in Dublin for one year, and earned her specialized diploma in obstetrics and gynecology. In 1932, Kawkab returned to Egypt, and worked at Kitchener Hospital (now Shubra General Hospital), or “the Espitalia” as she called it. Her dream was for all the hospital staff members to be Egyptian nationals. In addition to gynecology, Kawkab worked in several specializations, including surgery and internal medicine.

Kawkab was invited, along with Suhair al-Qalamawi and Latifa Nagi, to the large ceremony organized by Hoda Shaarawy to celebrate the first women university graduates. Kawkab was aware of Hoda Shaarawy’s efforts, and the activities of the Women’s Union, but she was not involved with them. As she put it, “I had no relationship with the Women’s Union because my heart and my soul were into medicine and my work at the hospital. I followed its news, but I never participated because I was surrounded by the English. The hospital manager, the nurses, and the board of directors were mostly English. I knew that if I made a small mistake, they would get rid of me. I paid close attention to that because I wanted to be the Hospital Director one day. I would not get that chance if they got rid of me at such an early stage of my career. I was very careful of what I said and did.”

In 1938, the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Ali Ibrahim Pasha, sent Kawkab to Saudi Arabia, at the request of King Abd al-Aziz, to work as the private doctor of the King’s wives and daughters. She recalled her memories in Saudi Arabia, and the difficult living conditions she endured there. Upon her return to Egypt, Kawkab resumed her post at Kitchener Hospital, and became the hospital’s lead doctor. She recounted, “it was a very big deal to be the lead doctor in the hospital, and deal with the administration. One of the doctors used to say that I had two personalities, one very pleasant with the doctors, and another very rigid with the staff. But I was not rigid at all, to the contrary. The girls on the staff were like my daughters, and I wanted to train them to become nurses, managers, and supervisors. And I did! The hospital was run by these women I trained. They did a great job.”

Kawkab Hefni Nassif served as the Hospital Director, and developed it with the support of the board of directors. She took charge of training the new doctors, and established a nursery for the children of the hospital staff. She also founded the first nursing school in Egypt. Her dream came true in 1964, when the Egyptian University Hospital became officially affiliated with Egypt’s Ministry of Health. For Kawkab, her biggest life achievement was choosing a career in medicine, saying, “you can say that practicing medicine is what made me who I am.”