Fatma Moussa

Professor of English Literature and Translator

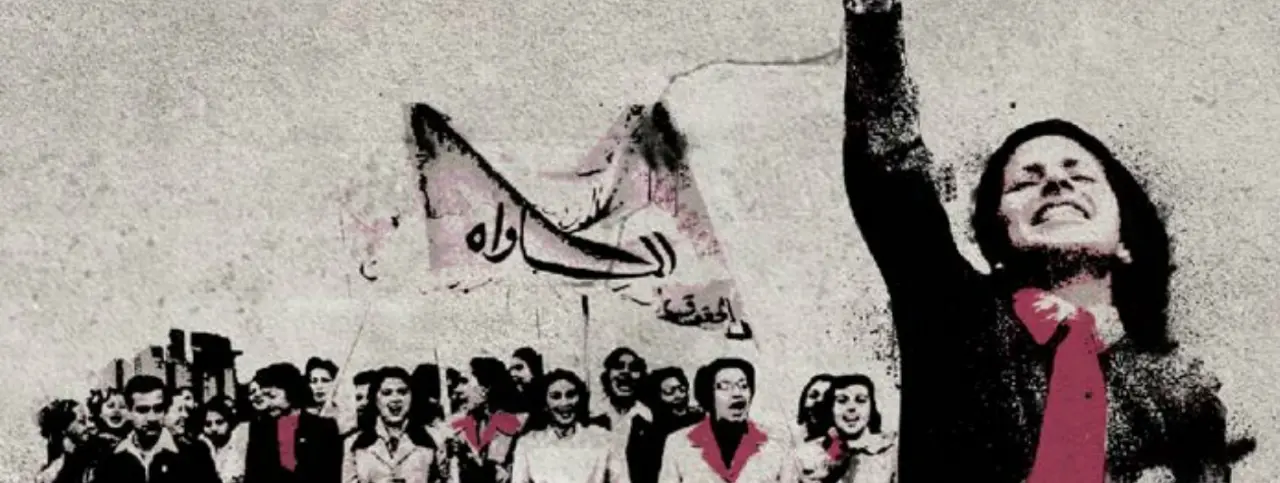

Dr. Fatma Moussa, a literary critic and a professor of English literature, is an Egyptian woman pioneer of modern translation. She graduated from the English Department at the Faculty of Arts, Cairo University in 1948, and was appointed to work there in 1952, despite the University’s objections to offering women teaching jobs. She earned her PhD in the English Language and Literature from Westfield College, London University in 1957. Fatma served as the Head of the English Department, and the Supervisor of the Translation Committee at the Supreme Council of Culture, in addition to working as the chief executive of the Egyptian Pen League. She collaborated with Etedal Othman and Radwa Ashour in a project titled Women’s Gateway “Saray al-Mar’a,” at Cairo’s International Book Fair. The project involved recording the life and achievements of a group of women pioneers, such as Aida Fahmi, Genevieve Sidaros, and Aisha Abd al-Rahman. In the interview, she spoke about her academic career.

Fatma was born on Mohamed Ali Street, in Cairo, as the eldest child to two highly intelligent parents, as she described them. Her father was born in 1899 in Upper Egypt. He was selected by the state to receive formal education in a school, but al-Omda, the Town Chief, intervened to stop him from leaving to school because he was the only son in the family. After his father’s death, he travelled to live in Cairo, and enrolled in a night school. He loved reading and writing, and passed this love down to his daughter, Fatma. As for Fatma’s mother, she was born in Alexandria, and never learned to read or write because she was not keen on education as a child, which was the main motivation behind her eagerness to offering her children with the best education. As a result, the mother moved Fatma from one school to the other seeking the best learning opportunity for her daughter, and securing her access to higher education.

Fatma attended primary school, where she was introduced to the English language for the first time by Mr. Geed. At first, she did not know a word of English, and did not understand the language at all. Yet, she always started on reading her school textbooks the moment she received them. Her relationship with the English language transformed, and she became her teacher’s source of pride. Fatma also attended al-Baheya al-Borhaneya School, where Abla Hamida, one of the women pioneers of education in Egypt, served as the Principal. Fatma finished her primary education in 1939, then attended Princess Fawzia Secondary School, which was a huge building, now the headquarters of the Egyptian Book Organization. Fatma recounted that this was a public school with annual fees of one Egyptian pound, yet offered high-quality education that was better than the education offered in the private schools that charged fees of twenty pounds.

Fatma talked about her teachers, saying “these women were mothers, and had a maternal presence in school, along with their strength and devotion to work.” She also spoke about the great influence of Principal Abla Ensaf Serry, another woman pioneer of education, and her impact on the intellectual development of the students. Abla Ensaf used to invite the school graduates to tell their stories and share their experiences with the schoolgirls. Among those graduates were pioneers such as Naeema al-Ayoubi and Atiyat al-Shafei who was the first Egyptian woman lawyer. The school graduates were also among the first group of women to enter Cairo University, among whom were Mofeeda Abdu, Zuhaira Abdeen, and Kawkab Hefni Nassif. Fatma was taught the English and French languages by English and French nationals, until one year, a number of Egyptian teachers arrived to school. These teachers were the first class of women to graduate from the Institute for Education, among them were Mary Salama and Zaynab Ramzi.

Fatma was fond of the school and education in general. She studied for five years to earn her high-school certificate, which was mandatory for girls, unlike the boys who studied only for four years. During those five years, Fatma engaged in various school activities, including theater and tennis, and spent her recess reading in the school library, which contained over 6000 books. This was the reason why Fatma got special treatment from Ms. Sage, the English librarian, who encouraged her love for reading, by allowing her to keep some of the books to read during the summer vacation. Ms. Sage also involved Fatma in the library duties, and in assisting the other students. Fatma stated that she read all the English literature before graduating high school, and that she kept in touch with Ms. Sage who later transferred to work in other cities outside Cairo. In her fifth year, Fatma decided to specialize in the English language, and train for a job in journalism upon Ms. Sage’s advice, despite her success in mathematics. Her father even received a letter from the Minister of Education nominating Fatma to join the mathematics program in Helwan.

However, Fatma joined the Department of English Language and Literature at Cairo University in 1944, and found no difficulty in keeping up with her studies. As she put it, “studying at the English Department was easy for me, and I cherished learning there.” Like in school, Fatma spent her time at the university library, and sometimes stayed until the library’s closing hours at nine in the evening. She studied under several English nationals, who taught at the university as an alternative to fulfilling the military service. Among these English professors were authors, such as P. H. Newby, whom Fatma did not know at the time as a writer, and Martin Lings with whom Fatma disagreed a lot. She recalled Lings once telling her that she was too ignorant to argue with him, but they met years later at the British Museum and became friends. Fatma recalled that in 1951 when Mostafa al-Nahass Pasha abrogated the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty, her English professors had left Egypt with the withdrawal of the English troops in 1946, following the tragedy of Abbas Bridge. She added that she never had the courage to join any of the protests outside the university walls, saying “the only time I marched outside the university was in the funerary procession of Taha Hussein.”

Her class at the Department encompassed forty students, all of whom were women except for one male student who transferred without graduating. Her class was also among the first classes to comprise more female students than male. She graduated top of her class, and was the only student to attend the excellence program, in which she studied under Dr. Louis Awad. Despite her eligibility for a teaching post at Cairo University, Fatma was not appointed upon her graduation because the university administration at that time was not willing to hire women lecturers. As a result, she joined the Ministry of Education, and worked as a teacher at the Nile Secondary School in Shubra, for a salary of eleven Egyptian pounds, then at al-Qubba al-Khediweyya School. While working as a teacher, she registered for a master’s degree in 1951, then requested a two-year unpaid leave to focus on her studies, and was granted the leave by Taha Hussein, who was the Minister of Education at the time.

In January 1952, a decree was passed appointing her as a Teaching Assistant at the English Department, then another appointing her colleague Ensaf al-Massry, who received a scholarship in the USA, and settled there. Fatma perceived her appointment as a direct result of what she described as the “revolutionary flow” in Egypt, with the abrogation of the peace treaty, the Cairo fire, then the July 23rd 1952 Revolution.

Fatma, and her colleagues Dr. Rashad Rushdy and Dr. Louis Awad were vigilant about introducing the Arabic literature into the English Department through extracurricular activities. She also completely rejected restricting admission into the English Department to the graduates of foreign schools, saying, “It cannot be. I was not a graduate of a foreign school, neither was any of Rashad Rushdy, Abd al-Azeez Hamouda, nor Mohamed Enani. The people who learned and knew English well graduated from Arabic schools, with good education in the English language.” Fatma recognized the significant role played by the English Department at Cairo University in enriching the Egyptian culture, particularly Dr. Rashad Rushdy’s attention to theater, literary criticism, as well as scientific research that was nonexistent under the English administration. Fatma described the transformation in the Department, saying “the English Department was the center for literary activities, both inside and outside the university.” This was particularly true with the introduction of the translation courses that were taught in all levels of the undergraduate program, in addition to the Arabic poetry and theater activities. For Fatma, the period of the 1950s and 1960s was very vibrant for literature, poetry, and theater, especially the 1960s when there was one holistic national project.

In 1957, Fatma traveled to England to earn her PhD, producing a dissertation on the orientalists, which was published as a book in 1962, and deposited in the Department’s library that was founded by Dr. Magdy Wahba. She later traveled again to England on a scientific mission.

Fatma married Dr. Mostafa Soueif, a Psychology Professor at Cairo University, whom she herself chose as a partner, and had three children together. She found her joy in her children, and did not experience any conflict between her marital happiness and her successful career, despite the hardships. Choosing the right partner was key for her.

Fatma Mousa expressed great pride in studying at the English Department, and in being the youngest among the contributors who revitalized it. She was also proud of her success in managing her work, while fulfilling her duties as a wife and a mother, explaining, “I reaped the rewards of being a wife, a mother, and a world literature scholar, while sharing my thoughts on world issues. If you look at my kitchen, you will find a big table with a pile of papers on it.”