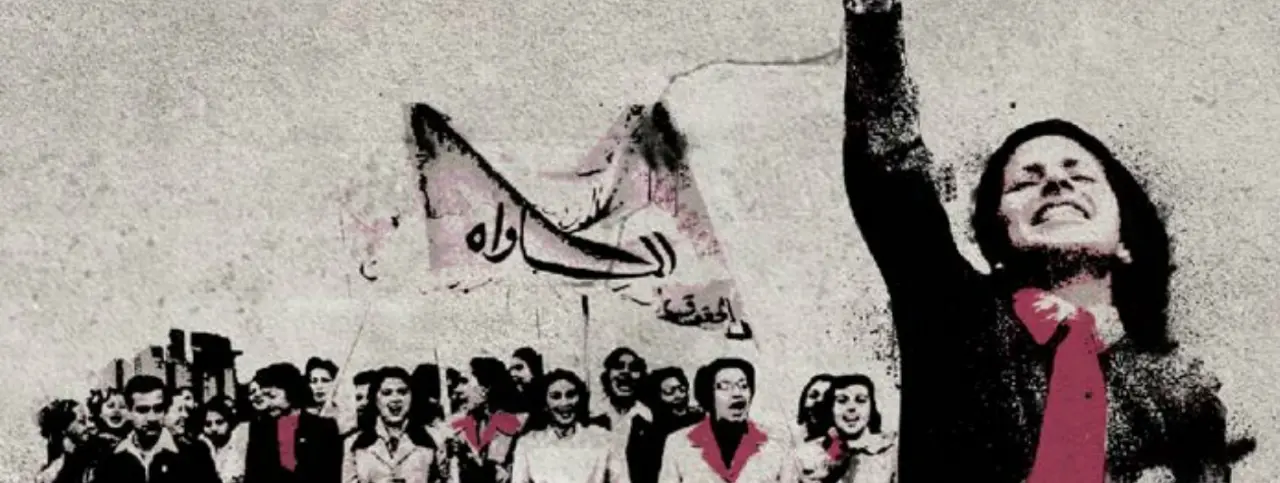

Shahira Mehrez

Owner of a chain store of Egyptian heritage artifacts

Shahira Mehrez is an Islamic art expert, fashion designer, and the owner of a chain store that sells artifacts inspired by the Egyptian heritage. She has been keen on preserving Egyptian handicrafts, folklore, and traditional costumes from the ancient Egyptian civilization to the present day. At first, she decided to study chemistry at Helwan University, acting upon her belief that women are able to break into any field of their choice. However, over time, she discovered her love and interest in Egyptian heritage and folklore, and so shifted her career path, and earned a master’s degree. Shahira decided to broaden her research, and started collecting different types of traditional costumes from twelve different regions in Egypt. In the interview, she shared her journey as one of the first women interested in Egypt’s history and heritage.

Shahira was born into an affluent family, which she described saying, “my family is considered feudal, not the huge kind of feudalist family, though. Despite its feudal status, my family rejected the British occupation.” She also described her father and mother as loyal patriots, recalling her mother’s boycott of the English products, refusing to allow any English product into their family house during the time of the English occupation. Shahira recounted a conversation with her mother, stating, “I remember when I was young, my mother and I used to walk this way. On one side was my paternal grandfather’s house, and on the other side was my maternal grandmother’s house. We used to walk the distance between those two houses before the Revolution. Once, when I was 6 or 7 years old, we came across an English soldier, and she told me that if he assaulted us, we would not be able to get justice, because our country was occupied. My mother told me then that there was something called a mixed court, and that these mixed courts ruled in favor of the people who were stealing our country from us. We did not have a country. We were an occupied land.”

Shahira attended French schools, and French was often the language spoken at home. However, her family was keen on teaching her the Arabic language, and hired a religion teacher to help Shahira memorize the Quran. Despite the effort, Shahira spent a long part of her life unable to master the Arabic language. She believed that this mixture created contradictory feelings in her, ranging between belonging and alienation at the same time. She lamented the fading interest in the Arabic language these days, saying, “I can sense the current tragedy. The children in all schools now do not know the Arabic language, and the steps my generation walked forward, they walked back in reverse, with more foreign schools that make you feel like a second-grade citizen.”

Shahira also spoke about the 1952 Revolution and its impact on her. One of the major advantages of the Revolution, as she said, was the education offered to her generation, as well as the interest in the girls’ education and work. Girls became primarily dependent on their own selves, instead of relying on the property of their families or husbands. On the Revolution, Shahira recounted, “I was also the generation of the Revolution. My father was scared to death of the Revolution, and the new socialist laws that were declared by Abd al-Nasser on television every year, between July 23rd and July 26th. They called it Socialist July. At the time, people would sit waiting for their names to be called, so they would know if they were going to be placed under house arrest, or under guard, or if they were going to be denied their civil rights. The pressure was terrible. Every year on the 23rd of July, we used to take my father to the hospital. Three years in a row, then on the fourth he died. Nevertheless, I was part of the generation that believed in the principles of the Revolution, but ever since I was young, I thought the way they were applied into practice was wrong. The Revolution was created by Abd al-Halim Hafez’s songs than by actual change. We were only selling songs. I felt that there was some kind of mismanagement of the state. I was not upset because they took the land from us. I was upset because of the fragmentation of agricultural ownership. I was a well-educated 20-year-old young woman, and I knew that the land that was managed as one, two, or three thousand acres would not be managed as five acres. The change destroyed the country’s agriculture. It was clear since then. That is why I was not a Nasserist.”

Shahira chose to study chemistry in the sciences department at the American University in Cairo, and attributed her decision to her inability to enroll into an Egyptian university, where the education was offered entirely in Arabic. She recalled the interest of the American University in the Arabic language at the time, saying, “they had a professor called Dr. Noweihy, God rest his soul. He was a genius. He could compete with teachers of the English and French literature.” Shahira tried to learn Arabic on her own as well. After completing her studies in chemistry, she discovered in herself a preoccupation with the idea of identity, and decided to obtain a master’s degree in Islamic archaeology from the American University. She also decided to study for her PhD in England, and attended Oxford University in 1974. Yet, she preferred to return to Egypt, and launch her own handicraft project instead, since she always had a desire to reconnect with the Egyptian countryside, from which she was separated in her childhood. She also decided to engage in a deeper study of the Egyptian folklore.

Shahira worked for a while as a freelance teacher at Helwan University, but did not last long. She was interested in collecting cultural heritage artifacts, and she also decided to open her own store. Shahira recounted that she hired the prominent Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy to design her house, and explained her huge influence on her at that time, saying, “He was a wonderful human being. He helped me a lot on bringing together the two sides of my character: my French Western culture, and my sense of belonging to Egypt. I felt a terrible conflict, because to the French, I was Egyptian, and to the Egyptians, I was French. I felt that this was a disaster. When I met Hassan Fathy, he told me that this was not a disaster. It was the exact opposite. What do you call the opposite of a disaster in Arabic? An advantage…it was a blessing that I had two civilizations, and that I could move from one to the other as I wanted.” Shahira added, “through Hassan, I realized that identity is not only about poetry, speeches, and politics. Identity is in character formation. I also learned that arts are not luxuries, and that art is linked to identity, to self-pride, and to the person’s sense of dignity. Without that, there is a sense of inferiority.”

Shahira Mehrez spoke about her interest in the Egyptian heritage and civilization, and the problems she encountered in the historicization process, which, as she stated, was mostly done by foreigners. As she put it, “people say that we are one of the ancient civilizations, but not the oldest. They claim that China or Mesopotamia is the oldest civilization, but that is not true. They date our history back to the time of the first dynasties, but these dynasties built the pyramids. In order for these early dynasties to have built a pyramid, they would need at least 800 to 1000 years, if not more. That is why now the Egyptian history is recognized as dating back 10 thousand years, and maybe more. I will tell you because I am a woman interested in heritage. Go to the Egyptian Museum, and you will see that all the objects from the pre-dynastic era were created with the utmost mastery. It is impossible to believe that it took only 5000 years for the ancient Egyptians to hold a piece of granite, and sculpt it into a perfectly symmetrical bowl, one you could not even create with a computer. They cannot possibly tell us that our history is only 5000 years. No way.”