Zaynab Ezzat

Social work pioneer

Zaynab Ezzat is an Egyptian woman pioneer, and the founder of the Social Association for Productive Families, the League for Social Reform, Save the Children Organization, and al-Hanan Organization for Social Services. Zaynab was also an active member of the Red Crescent. She worked directly with low-income families to raise their standards of living, and supervised the organization of temporary and permanent exhibitions. In the interview, she spoke of her education, and shared the milestones of her social work career.

Zaynab was born in Hamamat al-Qobba district, in Cairo. Her mother was a member of the Muslim Women’s Association, and was among the first graduating class of al-Saniya School, with Lady Gamila Attia and Lady Hadiya Barakat. Zaynab’s father was a political activist, who worked alongside Mustafa Kamel, and participated in the 1919 Revolution. Zaynab recalled her parents’ attention to education, saying, “my family, and my social circle as a whole, appreciated education a lot. Maybe it is just my family or my social circle. I used to be surprised by people -who are not from our social circle- who paid attention to boys, but not the girls. We were not like that. Boys and girls were exactly the same.”

At the age of five, Zaynab attended the mixed-sex kindergarten in Heliopolis, and described this period, saying, “we had a good education, meaning we used to leave kindergarten having learned how to read and write. We wrote well, and we read well.” She then attended Heliopolis Primary School for Girls for four years. It was a public school, in which the entire teaching staff was made up of Egyptian nationals, under the leadership of the Principal Naima Ahmed. Zaynab completed her secondary education at the College for Girls in Giza, which was later moved to Zamalek. At the College for Girls, the Dean was a Swiss national, and the education lasted for four years, followed by another two years to obtain the diploma. After earning her diploma, Zaynab attended Saint Clair’s College. Despite her mother’s keenness on education, she refused to allow Zaynab to pursue a university degree, due to her objection to the mixed-sex education.

Zaynab spoke about her teachers Madame Berg, Ms. Neama Kashmiri, and Ms. Hamida Sadiq, and their devotion to their students and their education. She recalled that the School Secretary at that time was Dr. Aisha Abd al-Rahman, Bent al-Shatie’ who worked at the school while studying for her university degree. Zaynab had great admiration for Dr. Aisha, saying, “in my opinion, and because she was a rural girl, who came from the countryside, I really think she fought so hard to succeed. She did not care for traditions, and she fought to learn, to work, and to complete her studies while working.” Among Zaynab’s classmates were Fawqia Taymour, Bahia al-Fransawi, Isaad Diab, Wagiha Shafie, and Souad Allam.

Zaynab loved to read both Arabic and English novels, and read many novels by Mustafa Lutfi al-Manfaluti and Taha Hussein. She also loved reading the poetry by Ahmed Shawky and Hafez Ibrahim. She recalled that Rose al-Youssef Magazine was banned at her home.

Zaynab accredited to her teacher Madame Berg her inspiration to engage in social work. Madam Berg used to encourage the students to visit the orphanages. With her father’s support and motivation, Zaynab continued to visit the orphanages, until one day, Mohamed Allouba Pasha, her father’s friend, suggested that she volunteered at Save the Children, which was an organization that he headed. Zaynab became an active member of the Organization, alongside her parents, then served on its board of directors following the 1952 Revolution.

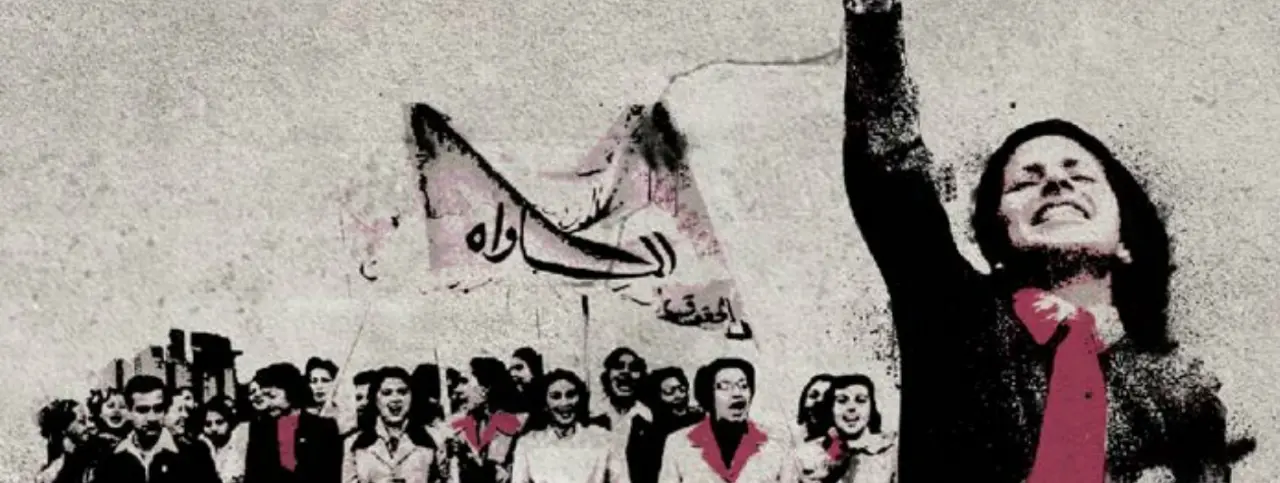

Zaynab recounted that during her early engagement in social work, she attended one of the meetings at Hoda Shaarawy’s organization, and was fascinated by Hoda Shaarawy. As she put it, “when I started getting involved with the social organizations, I attended a group meeting for all the organizations. It was held at Hoda Shaarawy’s organization. I was happy to attend. I was young, almost 18 years old or something. I went there with my family’s car. I was dying to see Hoda Shaarawy. I mean, I was really hoping to see her, after hearing about everything she has done. She was the first one to take off the face veil, and the first one to march in demonstrations. So, when I saw her, I kept staring at her. I was fixated on her that she noticed me looking at her. She asked me about my name, and I told her my name is Zaynab Ezzat. She then kept talking to me. Imagine that! She was very nice.”

In 1956, Zaynab established the Arab Labor Organization, in collaboration with Egyptians and Arabs, for the aim of promoting cultural and social exchange between the peoples of different countries. After some of the Arab countries boycotted Egypt, the name of the Organization changed to al-Hanan Organization for Social Services, and its aims modified accordingly to focus on providing social service. The Organization encompassed a club for the elderly, a nursery, a dorm for expatriate female students, and an arts and crafts training center.

In the 1970s, Zaynab presided over the League for Social Reform, which was founded by the Minister of Education, Hassan Pasha al-Ashmawy, in the late 1930s. She assumed the presidency of the League at the request of the Minister of Social Affairs. On the League and its activities, Zaynab said, “it has 11 facilities around Cairo, in al-Zeitoun, al-Helmeya, Heliopolis, Shubra, Masarrah, Zeinhom, al-Sharabeyah, al-Sayeda Zeinab, and Misr al-Qadima. Each facility offers multiple services, including orphanages, training centers, literacy classes, and accommodation for expatriate students.”

Affiliated with the League were the Social Work Institute and the Higher Institute for Administration and Secretarial Education. Later, the League included the Popular Education Institute, which offered literacy classes and vocational training for children who were first offenders. Zaynab spoke about this Institute saying, “instead of going to prison, the children who are first offenders come to the Popular Education Institute. We teach them to read and write, and give them carpentry, printing, and plumbing classes. It is such a beautiful thing. They leave as working citizens.”

Zeinab headed multiple social organizations, including Save the Children, al-Hanan for Social Services, the Productive Families, and the League for Social Reform, in addition to serving as the Secretary-General of the Red Crescent, and the Chairwoman of the Hospitals Committee. She worked as an active member of the Egyptian-Romanian Friendship Association, and the National Council for Women.

Zaynab spoke about society’s view of the work done by NGOs and charity organizations before the July 1952 Revolution, recounting, “before the revolution, society did not take women in social organizations seriously. These women were not perceived as really serious about their work. Instead, society saw our work as vanity. We were looked at as vain women with so much time on our hands, women who had empty lives, and did not know what to do with our time and so we go to organizations. We actually could go to the club, for example, instead of struggling to collect donations. It was difficult to keep raising funds, although at that time people were very rich, but society before the Revolution did not take social work seriously. I lived through both eras, before and after, and I could tell.”

Zaynab also recalled the role played by a number of pioneering feminists, such as Lady Saniya Anan, Doria Shafiq, and Dr. Aisha Rateb, Aziza Hussein, Laila Doss, and the author Neama Rashid, who established a political party alongside her social work. Zaynab expressed her pride in her achievements, but she was mostly proud of the accomplishments attained by the Egyptian women in the public sphere. As she put it, “I want to tell Egyptian women to accomplish more, and to do more work because the Egyptian woman, the working woman, must always prove that she deserves the rights she earned. I am really so proud of the Egyptian women who represent our country well abroad. They have reached wonderful positions that I hope they will keep, and further advance in their careers. Who knows, maybe the future generations would get to see women judges. This is what I hope, God willing, they will get there. To my daughters, to the young Egyptian women, I want to tell them that this is our country, and that they will find great joy in volunteering for any social cause. It is a very very good thing to do. They do not have to devote all their time to it, just once a week, not even that, I say once a month. Then, a bit but bit, they will find it in their heart to be more willing. The women who still engage in social work are not many, and they are not young. They are mostly over forty-five, but they still have things to do, yet they come whenever they have a half day off. They come to work, and give back. They tell me that working brings them joy. They come to bring happiness to themselves. That is why I would like to invite our young women, my daughters, to engage in volunteer work. They will gain two things: God’s blessings, and the chance to serve our country for nothing in return. It is a very nice feeling. I feel bad that the wonderful work done by thousands of organizations will one day be gone. We have the frontliners, but we need more. We need second line, and third line, to follow the generation of women currently working. This is my main concern right now. I wish that girls and young women take more interest in this great work. I wish Egyptian women all the success, all the achievements, in all fields.”